Robin of Loxley

Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is depicted as being of noble birth, and in modern retellings he is sometimes depicted as having fought in the Crusades before returning to England to find his lands taken by the Sheriff. In the oldest known versions he is instead a member of the yeoman class. Traditionally depicted dressed in Lincoln green, he is said to have robbed from the rich and given to the poor.

| Robin Hood | |

|---|---|

| Tales of Robin Hood and his Merry Men character | |

Woodcut of Robin Hood, from a 17th-century broadside | |

| First appearance | 13th/14th century AD |

| Created by | anonymous balladeers |

| Portrayed by |

|

| Voiced by | |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias |

|

| Occupation | Variable: yeoman, archer, outlaw later stories: nobleman |

| Affiliation | Loyal to Richard the Lionheart |

| Spouse | Maid Marian (in some stories) |

| Significant other | Maid Marian |

| Religion | Christian |

| Nationality | English |

Through retellings, additions, and variations, a body of familiar characters associated with Robin Hood has been created. These include his lover, Maid Marian, his band of outlaws, the Merry Men, and his chief opponent, the Sheriff of Nottingham. The Sheriff is often depicted as assisting Prince John in usurping the rightful but absent King Richard, to whom Robin Hood remains loyal. His partisanship of the common people and his hostility to the Sheriff of Nottingham are early recorded features of the legend, but his interest in the rightfulness of the king is not, and neither is his setting in the reign of Richard I. He became a popular folk figure in the Late Middle Ages, and the earliest known ballads featuring him are from the 15th century (1400s).

There have been numerous variations and adaptations of the story over the subsequent years, and the story continues to be widely represented in literature, film, and television. Robin Hood is considered one of the best known tales of English folklore.

The historicity of Robin Hood is not proven and has been debated for centuries. There are numerous references to historical figures with similar names that have been proposed as possible evidence of his existence, some dating back to the late 13th century. At least eight plausible origins to the story have been mooted by historians and folklorists, including suggestions that "Robin Hood" was a stock alias used by or in reference to bandits.

Ballads and tales

The first clear reference to "rhymes of Robin Hood" is from the alliterative poem Piers Plowman, thought to have been composed in the 1370s, followed shortly afterwards by a quotation of a later common proverb,[1] "many men speak of Robin Hood and never shot his bow",[2] in Friar Daw's Reply (c.1402)[3] and a complaint in Dives and Pauper (1405-1410) that people would rather listen to "tales and songs of Robin Hood" than attend Mass.[4] Robin Hood is also mentioned in a famous Lollard tract (Cambridge University Library MS Ii.6.26) dated to the first half of the fifteenth century[5] (thus also possibly predating his other earliest historical mentions)[6] alongside several other folk heroes such as Guy of Warwick, Bevis of Hampton and Sir Lybeaus.[7]

However, the earliest surviving copies of the narrative ballads that tell his story date to the second half of the 15th century, or the first decade of the 16th century. In these early accounts, Robin Hood's partisanship of the lower classes, his devotion to the Virgin Mary and associated special regard for women, his outstanding skill as an archer, his anti-clericalism, and his particular animosity towards the Sheriff of Nottingham are already clear.[8] Little John, Much the Miller's Son and Will Scarlet (as Will "Scarlok" or "Scathelocke") all appear, although not yet Maid Marian or Friar Tuck. The latter has been part of the legend since at least the later 15th century, when he is mentioned in a Robin Hood play script.[9]

In modern popular culture, Robin Hood is typically seen as a contemporary and supporter of the late-12th-century king Richard the Lionheart, Robin being driven to outlawry during the misrule of Richard's brother John while Richard was away at the Third Crusade. This view first gained currency in the 16th century.[10] It is not supported by the earliest ballads. The early compilation, A Gest of Robyn Hode, names the king as 'Edward'; and while it does show Robin Hood accepting the King's pardon, he later repudiates it and returns to the greenwood.[11][12] The oldest surviving ballad, Robin Hood and the Monk, gives even less support to the picture of Robin Hood as a partisan of the true king. The setting of the early ballads is usually attributed by scholars to either the 13th century or the 14th, although it is recognised they are not necessarily historically consistent.[13]

The early ballads are also quite clear on Robin Hood's social status: he is a yeoman. While the precise meaning of this term changed over time, including free retainers of an aristocrat and small landholders, it always referred to commoners. The essence of it in the present context was "neither a knight nor a peasant or 'husbonde' but something in between".[14] Artisans (such as millers) were among those regarded as 'yeomen' in the 14th century.[15] From the 16th century on, there were attempts to elevate Robin Hood to the nobility, such as in Richard Grafton's Chronicle at Large;[16] Anthony Munday presented him at the very end of the century as the Earl of Huntingdon in two extremely influential plays, as he is still commonly presented in modern times.[17]

As well as ballads, the legend was also transmitted by 'Robin Hood games' or plays that were an important part of the late medieval and early modern May Day festivities. The first record of a Robin Hood game was in 1426 in Exeter, but the reference does not indicate how old or widespread this custom was at the time. The Robin Hood games are known to have flourished in the later 15th and 16th centuries.[18] It is commonly stated as fact that Maid Marian and a jolly friar (at least partly identifiable with Friar Tuck) entered the legend through the May Games.[19]

Early ballads

The earliest surviving text of a Robin Hood ballad is the 15th-century "Robin Hood and the Monk".[20] This is preserved in Cambridge University manuscript Ff.5.48. Written after 1450,[21] it contains many of the elements still associated with the legend, from the Nottingham setting to the bitter enmity between Robin and the local sheriff.

The first printed version is A Gest of Robyn Hode (c. 1500), a collection of separate stories that attempts to unite the episodes into a single continuous narrative.[22] After this comes "Robin Hood and the Potter",[23] contained in a manuscript of c. 1503. "The Potter" is markedly different in tone from "The Monk": whereas the earlier tale is "a thriller"[24] the latter is more comic, its plot involving trickery and cunning rather than straightforward force.

Other early texts are dramatic pieces, the earliest being the fragmentary Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham[25] (c. 1475). These are particularly noteworthy as they show Robin's integration into May Day rituals towards the end of the Middle Ages; Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham, among other points of interest, contains the earliest reference to Friar Tuck.

The plots of neither "the Monk" nor "the Potter" are included in the Gest; and neither is the plot of "Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne", which is probably at least as old as those two ballads although preserved in a more recent copy. Each of these three ballads survived in a single copy, so it is unclear how much of the medieval legend has survived, and what has survived may not be typical of the medieval legend. It has been argued that the fact that the surviving ballads were preserved in written form in itself makes it unlikely they were typical; in particular, stories with an interest for the gentry were by this view more likely to be preserved.[26] The story of Robin's aid to the 'poor knight' that takes up much of the Gest may be an example.

The character of Robin in these first texts is rougher edged than in his later incarnations. In "Robin Hood and the Monk", for example, he is shown as quick tempered and violent, assaulting Little John for defeating him in an archery contest; in the same ballad Much the Miller's Son casually kills a 'little page' in the course of rescuing Robin Hood from prison.[27] No extant ballad early actually shows Robin Hood 'giving to the poor', although in a "A Gest of Robyn Hode" Robin does make a large loan to an unfortunate knight, which he does not in the end require to be repaid;[28] and later in the same ballad Robin Hood states his intention of giving money to the next traveller to come down the road if he happens to be poor.

- Of my good he shall haue some,

- Yf he be a por man.[29]

As it happens the next traveller is not poor, but it seems in context that Robin Hood is stating a general policy. The first explicit statement to the effect that Robin Hood habitually robbed from the rich to give the poor can be found in John Stow's Annales of England (1592), about a century after the publication of the Gest.[30][31] But from the beginning Robin Hood is on the side of the poor; the Gest quotes Robin Hood as instructing his men that when they rob:

- loke ye do no husbonde harme

- That tilleth with his ploughe.

- No more ye shall no gode yeman

- That walketh by gren-wode shawe;

- Ne no knyght ne no squyer

- That wol be a gode felawe.[11][12]

And in its final lines the Gest sums up:

- he was a good outlawe,

- And dyde pore men moch god.

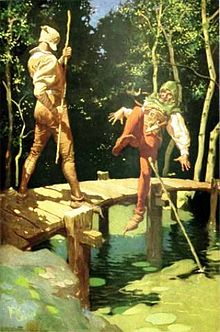

Within Robin Hood's band, medieval forms of courtesy rather than modern ideals of equality are generally in evidence. In the early ballad, Robin's men usually kneel before him in strict obedience: in A Gest of Robyn Hode the king even observes that 'His men are more at his byddynge/Then my men be at myn.' Their social status, as yeomen, is shown by their weapons: they use swords rather than quarterstaffs. The only character to use a quarterstaff in the early ballads is the potter, and Robin Hood does not take to a staff until the 17th-century Robin Hood and Little John.[32]

The political and social assumptions underlying the early Robin Hood ballads have long been controversial. It has been influentially argued by J. C. Holt that the Robin Hood legend was cultivated in the households of the gentry, and that it would be mistaken to see in him a figure of peasant revolt. He is not a peasant but a yeoman, and his tales make no mention of the complaints of the peasants, such as oppressive taxes.[33] He appears not so much as a revolt against societal standards as an embodiment of them, being generous, pious, and courteous, opposed to stingy, worldly, and churlish foes.[34] Other scholars have by contrast stressed the subversive aspects of the legend, and see in the medieval Robin Hood ballads a plebeian literature hostile to the feudal order.[35]

Early plays, May Day games and fairs

By the early 15th century at the latest, Robin Hood had become associated with May Day celebrations, with revellers dressing as Robin or as members of his band for the festivities. This was not common throughout England, but in some regions the custom lasted until Elizabethan times, and during the reign of Henry VIII, was briefly popular at court.[36] Robin was often allocated the role of a May King, presiding over games and processions, but plays were also performed with the characters in the roles,[37] sometimes performed at church ales, a means by which churches raised funds.[38]

A complaint of 1492, brought to the Star Chamber, accuses men of acting riotously by coming to a fair as Robin Hood and his men; the accused defended themselves on the grounds that the practice was a long-standing custom to raise money for churches, and they had not acted riotously but peaceably.[39]

It is from the association with the May Games that Robin's romantic attachment to Maid Marian (or Marion) apparently stems. A "Robin and Marion" figured in 13th-century French 'pastourelles' (of which Jeu de Robin et Marion c. 1280 is a literary version) and presided over the French May festivities, "this Robin and Marion tended to preside, in the intervals of the attempted seduction of the latter by a series of knights, over a variety of rustic pastimes".[40] In the Jeu de Robin and Marion, Robin and his companions have to rescue Marion from the clutches of a "lustful knight".[41] This play is distinct from the English legends.[36] although Dobson and Taylor regard it as 'highly probable' that this French Robin's name and functions travelled to the English May Games where they fused with the Robin Hood legend.[42] Both Robin and Marian were certainly associated with May Day festivities in England (as was Friar Tuck), but these may have been originally two distinct types of performance – Alexander Barclay in his Ship of Fools, writing in c. 1500, refers to 'some merry fytte of Maid Marian or else of Robin Hood' – but the characters were brought together.[43] Marian did not immediately gain the unquestioned role; in Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valor, and Marriage, his sweetheart is "Clorinda the Queen of the Shepherdesses".[44] Clorinda survives in some later stories as an alias of Marian.[45]

The earliest preserved script of a Robin Hood play is the fragmentary Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham[25] This apparently dates to the 1470s and circumstantial evidence suggests it was probably performed at the household of Sir John Paston. This fragment appears to tell the story of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne.[46] There is also an early playtext appended to a 1560 printed edition of the Gest. This includes a dramatic version of the story of Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar and a version of the first part of the story of Robin Hood and the Potter. (Neither of these ballads are known to have existed in print at the time, and there is no earlier record known of the "Curtal Friar" story). The publisher describes the text as a 'playe of Robyn Hood, verye proper to be played in Maye games', but does not seem to be aware that the text actually contains two separate plays.[47] An especial point of interest in the "Friar" play is the appearance of a ribald woman who is unnamed but apparently to be identified with the bawdy Maid Marian of the May Games.[48] She does not appear in extant versions of the ballad.

Robin Hood on the early modern stage

James VI of Scotland was entertained by a Robin Hood play at Dirleton Castle produced by his favourite the Earl of Arran in May 1585, while there was plague in Edinburgh.[49]

In 1598, Anthony Munday wrote a pair of plays on the Robin Hood legend, The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington (published 1601). These plays drew on a variety of sources, including apparently "A Gest of Robin Hood", and were influential in fixing the story of Robin Hood to the period of Richard I. Stephen Thomas Knight has suggested that Munday drew heavily on Fulk Fitz Warin, a historical 12th century outlawed nobleman and enemy of King John, in creating his Robin Hood.[50] The play identifies Robin Hood as Robert, Earl of Huntingdon, following in Richard Grafton's association of Robin Hood with the gentry,[51] and identifies Maid Marian with "one of the semi-mythical Matildas persecuted by King John".[52] The plays are complex in plot and form, the story of Robin Hood appearing as a play-within-a-play presented at the court of Henry VIII and written by the poet, priest and courtier John Skelton. Skelton himself is presented in the play as acting the part of Friar Tuck. Some scholars have conjectured that Skelton may have indeed written a lost Robin Hood play for Henry VIII's court, and that this play may have been one of Munday's sources.[53] Henry VIII himself with eleven of his nobles had impersonated "Robyn Hodes men" as part of his "Maying" in 1510. Robin Hood is known to have appeared in a number of other lost and extant Elizabethan plays. In 1599, the play George a Green, the Pinner of Wakefield places Robin Hood in the reign of Edward IV.[54] Edward I, a play by George Peele first performed in 1590–91, incorporates a Robin Hood game played by the characters. Llywelyn the Great, the last independent Prince of Wales, is presented playing Robin Hood.[55]

Fixing the Robin Hood story to the 1190s had been first proposed by John Major in his Historia Majoris Britanniæ (1521), (and he also may have been influenced in so doing by the story of Warin);[50] this was the period in which King Richard was absent from the country, fighting in the Third Crusade.[56]

William Shakespeare makes reference to Robin Hood in his late-16th-century play The Two Gentlemen of Verona. In it, the character Valentine is banished from Milan and driven out through the forest where he is approached by outlaws who, upon meeting him, desire him as their leader. They comment, "By the bare scalp of Robin Hood's fat friar, This fellow were a king for our wild faction!"[57] Robin Hood is also mentioned in As You Like It. When asked about the exiled Duke Senior, the character of Charles says that he is "already in the forest of Arden, and a many merry men with him; and there they live like the old Robin Hood of England". Justice Silence sings a line from an unnamed Robin Hood ballad, the line is "Robin Hood, Scarlet, and John" in Act 5 scene 3 of Henry IV, part 2. In Henry IV part 1 Act 3 scene 3, Falstaff refers to Maid Marian implying she is a by-word for unwomanly or unchaste behaviour.

Ben Jonson produced the incomplete masque The Sad Shepherd, or a Tale of Robin Hood[58] in part as a satire on Puritanism. It is about half finished and writing may have been interrupted by his death in 1637. It is Jonson's only pastoral drama, it was written in sophisticated verse and included supernatural action and characters.[59] It has had little impact on the Robin Hood tradition but needs mention as the work of a major dramatist.

The 1642 London theatre closure by the Puritans interrupted the portrayal of Robin Hood on the stage. The theatres would reopen with the Restoration in 1660. Robin Hood did not appear on the Restoration stage unless one includes "Robin Hood and his Crew of Souldiers" acted in Nottingham on the day of the coronation of Charles II in 1661. This short play adapts the story of the king's pardon of Robin Hood to refer to the Restoration.[60]

However, Robin Hood appeared on the 18th-century stage in various farces and comic operas.[61] Alfred, Lord Tennyson would write a four act Robin Hood play at the end of the 19th century, "The Forrestors". It is fundamentally based on the Gest but follows the tradition of placing Robin Hood as the Earl of Huntingdon in the time of Richard I, and making the Sheriff of Nottingham and Prince John rivals with Robin Hood for Maid Marian's hand.[62] The return of King Richard brings about a happy ending.

Broadside ballads and garlands

With the advent of printing came the Robin Hood broadside ballads. Exactly when they displaced the oral tradition of Robin Hood ballads is unknown but the process seems to have been completed by the end of the 16th century. Near the end of the 16th century an unpublished prose life of Robin Hood was written, and included in the Sloane Manuscript. Largely a paraphrase of the Gest, it also contains material revealing that the author was familiar with early versions of a number of the Robin Hood broadside ballads.[63] Not all of the medieval legend was preserved in the broadside ballads, there is no broadside version of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne or of Robin Hood and the Monk, which did not appear in print until the 18th and 19th centuries respectively. However, the Gest was reprinted from time to time throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

No surviving broadside ballad can be dated with certainty before the 17th century, but during that century, the commercial broadside ballad became the main vehicle for the popular Robin Hood legend.[64] These broadside ballads were in some cases newly fabricated but were mostly adaptations of the older verse narratives. The broadside ballads were fitted to a small repertoire of pre-existing tunes resulting in an increase of "stock formulaic phrases" making them "repetitive and verbose",[65] they commonly feature Robin Hood's contests with artisans: tinkers, tanners, and butchers. Among these ballads is Robin Hood and Little John telling the famous story of the quarter-staff fight between the two outlaws.

Dobson and Taylor wrote, 'More generally the Robin of the broadsides is a much less tragic, less heroic and in the last resort less mature figure than his medieval predecessor'.[66] In most of the broadside ballads Robin Hood remains a plebeian figure, a notable exception being Martin Parker's attempt at an overall life of Robin Hood, A True Tale of Robin Hood, which also emphasises the theme of Robin Hood's generosity to the poor more than the broadsheet ballads do in general.

The 17th century introduced the minstrel Alan-a-Dale. He first appeared in a 17th-century broadside ballad, and unlike many of the characters thus associated, managed to adhere to the legend.[44] The prose life of Robin Hood in Sloane Manuscript contains the substance of the Alan-a-Dale ballad but tells the story about Will Scarlet.

In the 18th century, the stories began to develop a slightly more farcical vein. From this period there are a number of ballads in which Robin is severely 'drubbed' by a succession of tradesmen including a tanner, a tinker, and a ranger.[56] In fact, the only character who does not get the better of Hood is the luckless Sheriff. Yet even in these ballads Robin is more than a mere simpleton: on the contrary, he often acts with great shrewdness. The tinker, setting out to capture Robin, only manages to fight with him after he has been cheated out of his money and the arrest warrant he is carrying. In Robin Hood's Golden Prize, Robin disguises himself as a friar and cheats two priests out of their cash. Even when Robin is defeated, he usually tricks his foe into letting him sound his horn, summoning the Merry Men to his aid. When his enemies do not fall for this ruse, he persuades them to drink with him instead (see Robin Hood's Delight).

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Robin Hood ballads were mostly sold in "Garlands" of 16 to 24 Robin Hood ballads; these were crudely printed chap books aimed at the poor. The garlands added nothing to the substance of the legend but ensured that it continued after the decline of the single broadside ballad.[67] In the 18th century also, Robin Hood frequently appeared in criminal biographies and histories of highwaymen compendia.[68]

Rediscovery of the Medieval Robin Hood: Percy and Ritson

In 1765, Thomas Percy (bishop of Dromore) published Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, including ballads from the 17th-century Percy Folio manuscript which had not previously been printed, most notably Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne which is generally regarded as in substance a genuine late medieval ballad.

In 1795, Joseph Ritson published an enormously influential edition of the Robin Hood ballads Robin Hood: A collection of all the Ancient Poems Songs and Ballads now extant, relative to that celebrated Outlaw.[69] [70] 'By providing English poets and novelists with a convenient source book, Ritson gave them the opportunity to recreate Robin Hood in their own imagination,'[71] Ritson's collection included the Gest and put the Robin Hood and the Potter ballad in print for the first time. The only significant omission was Robin Hood and the Monk which would eventually be printed in 1806. Ritson's interpretation of Robin Hood was also influential, having influenced the modern concept of stealing from the rich and giving to the poor as it exists today.[72][73][74][75] Himself a supporter of the principles of the French Revolution and admirer of Thomas Paine, Ritson held that Robin Hood was a genuinely historical, and genuinely heroic, character who had stood up against tyranny in the interests of the common people.[71]

In his preface to the collection, Ritson assembled an account of Robin Hood's life from the various sources available to him, and concluded that Robin Hood was born in around 1160, and thus had been active in the reign of Richard I. He thought that Robin was of aristocratic extraction, with at least 'some pretension' to the title of Earl of Huntingdon, that he was born in an unlocated Nottinghamshire village of Locksley and that his original name was Robert Fitzooth. Ritson gave the date of Robin Hood's death as 18 November 1247, when he would have been around 87 years old. In copious and informative notes Ritson defends every point of his version of Robin Hood's life.[76] In reaching his conclusion Ritson relied or gave weight to a number of unreliable sources, such as the Robin Hood plays of Anthony Munday and the Sloane Manuscript. Nevertheless, Dobson and Taylor credit Ritson with having 'an incalculable effect in promoting the still continuing quest for the man behind the myth', and note that his work remains an 'indispensable handbook to the outlaw legend even now'.[77]

Ritson's friend Walter Scott used Ritson's anthology collection as a source for his picture of Robin Hood in Ivanhoe, written in 1818, which did much to shape the modern legend.[78]

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood

In the 19th century, the Robin Hood legend was first specifically adapted for children. Children's editions of the garlands were produced and in 1820, a children's edition of Ritson's Robin Hood collection was published. Children's novels began to appear shortly thereafter. It is not that children did not read Robin Hood stories before, but this is the first appearance of a Robin Hood literature specifically aimed at them.[79] A very influential example of these children's novels was Pierce Egan the Younger's Robin Hood and Little John (1840).[80][81] This was adapted into French by Alexandre Dumas in Le Prince des Voleurs (1872) and Robin Hood Le Proscrit (1873). Egan made Robin Hood of noble birth but raised by the forestor Gilbert Hood.

Another very popular version for children was Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, which influenced accounts of Robin Hood through the 20th century.[82] Pyle's version firmly stamp Robin as a staunch philanthropist, a man who takes from the rich to give to the poor. Nevertheless, the adventures are still more local than national in scope: while King Richard's participation in the Crusades is mentioned in passing, Robin takes no stand against Prince John, and plays no part in raising the ransom to free Richard. These developments are part of the 20th-century Robin Hood myth. Pyle's Robin Hood is a yeoman and not an aristocrat.

The idea of Robin Hood as a high-minded Saxon fighting Norman lords also originates in the 19th century. The most notable contributions to this idea of Robin are Jacques Nicolas Augustin Thierry's Histoire de la Conquête de l'Angleterre par les Normands (1825) and Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1819). In this last work in particular, the modern Robin Hood—'King of Outlaws and prince of good fellows!' as Richard the Lionheart calls him—makes his debut.[83]

20th century onwards

The 20th century grafted still further details on to the original legends. The 1938 film, The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, portrayed Robin as a hero on a national scale, leading the oppressed Saxons in revolt against their Norman overlords while Richard the Lionheart fought in the Crusades; this movie established itself so definitively that many studios resorted to movies about his son (invented for that purpose) rather than compete with the image of this one.[84]

In 1953, during the McCarthy era, the Republican members of the Indiana Textbook Commission called for a ban of Robin Hood from all Indiana school books for promoting communism because he stole from the rich to give to the poor.[85][86]

Films, animations, new concepts and other adaptations

Walt Disney's Robin Hood

In the 1973 animated Disney film, Robin Hood, the title character is portrayed as an anthropomorphic fox voiced by Brian Bedford. Years before Robin Hood had even entered production, Disney had considered doing a project on Reynard the Fox. However, due to concerns that Reynard was unsuitable as a hero, animator Ken Anderson adapted some elements from Reynard into Robin Hood, thus making the title character a fox.[87]

Robin and Marian

The 1976 British-American film Robin and Marian, starring Sean Connery as Robin Hood and Audrey Hepburn as Maid Marian, portrays the figures in later years after Robin has returned from service with Richard the Lionheart in a foreign crusade and Marian has gone into seclusion in a nunnery. This is the first in popular culture to portray King Richard as less than perfect.

A Muslim among the Merry Men

Since the 1980s, it has become commonplace to include a Saracen (Arab/Muslim) among the Merry Men, a trend that began with the character Nasir in the 1984 ITV Robin of Sherwood television series. Later versions of the story have followed suit: the 1991 movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and 2006 BBC TV series Robin Hood each contain equivalents of Nasir, in the figures of Azeem and Djaq, respectively.[84] Spoofs have also followed this trend, with the 1990s BBC sitcom Maid Marian and her Merry Men parodying the Moorish character with Barrington, a Rastafarian rapper played by Danny John-Jules,[88] and Mel Brooks comedy Robin Hood: Men in Tights featuring Isaac Hayes as Asneeze and Dave Chappelle as his son Ahchoo. The 2010 movie version Robin Hood, did not include a Saracen character. The 2018 adaptation Robin Hood portrays the character of Little John as a Muslim named Yahya, played by Jamie Foxx. The character Azeem in the 1991 movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves was originally called Nasir, until a crew member who had worked on Robin of Sherwood pointed out that the Nasir character was not part of the original legend and was created for the show Robin of Sherwood. The name was immediately changed to Azeem to avoid any potential copyright issues.[citation needed]

Robin Hood in France

Between 1963 and 1966, French television broadcast a medievalist series entitled Thierry La Fronde (Thierry the Sling). This successful series, which was also shown in Canada, Poland (Thierry Śmiałek), Australia (The King's Outlaw), and the Netherlands (Thierry de Slingeraar), transposes the English Robin Hood narrative into late medieval France during the Hundred Years' War.[89

Mythology

There is at present little or no scholarly support for the view that tales of Robin Hood have stemmed from mythology or folklore, from fairies or other mythological origins, any such associations being regarded as later development.[123][124] It was once a popular view, however.[92] The "mythological theory" dates back at least to 1584, when Reginald Scot identified Robin Hood with the Germanic goblin "Hudgin" or Hodekin and associated him with Robin Goodfellow.[125] Maurice Keen[126] provides a brief summary and useful critique of the evidence for the view Robin Hood had mythological origins. While the outlaw often shows great skill in archery, swordplay and disguise, his feats are no more exaggerated than those of characters in other ballads, such as Kinmont Willie, which were based on historical events.[127]

Robin Hood has also been claimed for the pagan witch-cult supposed by Margaret Murray to have existed in medieval Europe, and his anti-clericalism and Marianism interpreted in this light.[128] The existence of the witch cult as proposed by Murray is now generally discredited.

Associated locations

List of traditional ballads

In popular culture

Main characters of the folklore

- Robin Hood (a.k.a. Robin of Loxley or Locksley)

- The band of "Merry Men"

- Maid Marian

- King Richard the Lionheart

- Prince John

- Sir Guy of Gisbourne

- The Sheriff of

Comments

Post a Comment